Codified narrative is the product of converting human-friendly narrative into computer-friendly code. In past blogs, I discussed my own approach towards this process of codification. Here, I will be covering the idea of spatial, temporal, and contextual distribution of codified narrative. I have never suggested that narrative can or should be used in place of quantitative data. However, I have reflected on how the quantitative regime has tended to dominate discourse; this has perhaps led to data being contextually constrained or deprived. Geography is a type of context that can shape the extent to which people interact with the world. Space provides a medium to distribute resources. It affects freedom. It can be involved in forced confinement. An office full of cubicles demonstrates control and dominance over space. When data loggers intercept and follow every computer in the office, it can be argued that lack of spatial deterrence has had the effect of consolidating control. The structures that would normally separate people and allow for some personal autonomy might be missing. Is an employer that controls every aspect of work necessarily more successful than its competitor? Not really. But centralized control over a narrative should be studied as an important evolution in human development; it is an increasingly important consideration for problem solving in human environments.

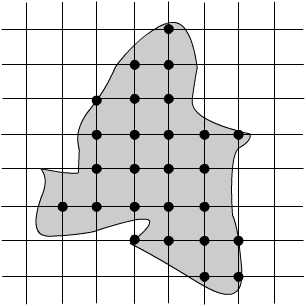

I will first give an example of how I think geographic codified narrative can enhance an existing quantitative regime. Imagine an island nation as in the image below where factories are distributed over a grid. Each factory has data – much likely to be quantitative in nature. If one were to select what data from which factories to include in a geographic sampling, codified narrative can make the selection possible using commonalities in business setting, behaviours, and objectives. It would be possible to examine a series of spatially-connected behaviours – using what I describe as “path analysis” – to pinpoint relevant quantitative data. If the data doesn’t exist, the codified narrative can provide a framework for its collection and potential use. (I will provide a more detailed discussion of this latter point a bit later.) It isn’t unusual for data to be deprived of context for example if it is designed for a specific purpose or perhaps more importantly a particular methodological approach. It is this purpose or approach that can taint the nature of the data such that all ensuing discourse is confined.

For me, the purpose of geography in relation to data reflects the purpose of narrative more broadly – to give data context. When dealing with a relational database, it would be safe to say that the data therein is highly decontextualized. Quantitative analysis routinely occurs in this type of disassociated data environment. Not always evident in this arrangement is the fact that “ownership” over the data generally belongs to those responsible for the database. The designer attaches structural meaning and relevance to the data that others are obligated to accept. For instance, if the designer says that a column means “customer sales,” it is unlikely that somebody will later say that it means “employee attendance.” Having established what should go in a column, it becomes tempting to assert the authority of the data defined by the column, delegitimizing those that might have less data or that might have different types. The data contained in the column for sales might be regarded as authoritative – as if the numbers represent sales in its totality of meaning. Yet perhaps some companies that maintain sales records don’t have the foggiest idea what brought about the sales.

Spatial Aspects of Ownership

These days before I post a blog, I do a Google search for matches based on the title. I found an interesting article (right here) written by some academics: it is about how informational sources can influence cultures. It reminds me of a debate about U.S. and Canadian television. Since Canada is right next to the U.S., and the latter has greater resources than the former, arguably Canadians have tended to be culturally influenced by U.S. television. These days the cultural inculcation takes place globally through informational resources such as Wikipedia and over the Internet. The absence of spatial constraints such as geographic boundaries creates a sort of dominance and authority by those responsible for the content.

Geography is frequently associated with space. But of course there are many ways to partition space. Codified narrative can be distributed geographically. Although narrative might be distributed using an existing spatial scheme, codification can give rise to other apparent geographies. For example, using BERLIN, my approach, which stands for “Behavioural Event Reconstruction Linguistic Interface for Narratives,” it would be possible to create behavioural geography. BERLIN code can be used to delineate geography. Or, geography can be used to select the code. On the application that I designed and wrote to handle codified narrative, I anticipated my future requirements by enabling the delineation of narrative using GPS coordinates.

In terms of spatial geography for my own design purposes, I have distinguished between the geography of the code and the geography of the conversation. A good way to make this distinction is to consider a logistics operation. The conversation might be about the routes taken by the delivery trucks. On the other hand, the people initiating the conversation might be in the shipping department and head office. On the surface, it might seem that the business aspect of this narrative is connected entirely to the performance of trucks. But there are likely important narrative contrast between the shipping department and head office that could give rise to administrative obstacles. Using BERLIN codified narrative the source is different from the conversation in the narrative. The source is stored as “spatial intersect data” whereas the conversation is stored as “behavioural event data.” These data types are exceptionally different in terms of both handling and appearance.

Type of Application

I provide an example of a geographic application above. This photograph of missing people was taken from a retailer with whom I have no affiliation except as a shopper. The details are difficult to read. Each bulletin contains a picture of the missing person, along with a description, and some general preamble such as location last seen. It is a worthwhile exercise maintaining this board. However, I appreciate the limitations of such a medium. I would describe these “postings” as non-narrative in nature. The general idea seems to be to raise awareness. Here, statistics might play a role in providing people a breakdown of those currently missing: e.g. a certain percentage having brown eyes, dark hair, a certain complexion, some specific facial characteristics. The narrative becomes an active consideration once people start calling the 1-800 number to provide their stories including dates, times, and locations.

Key Concepts

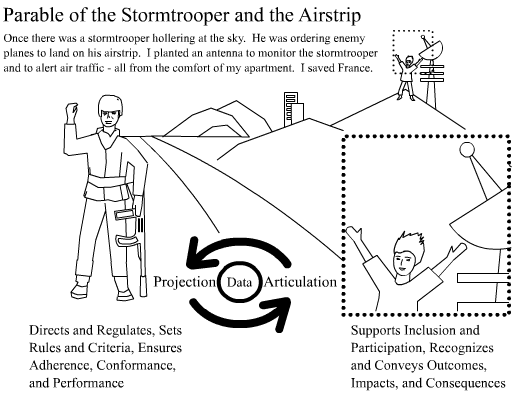

What sort of scenarios might be best examined geographically? To me, a good business example would involve a company operating a number of branches or stores. When quantitative data is collected, it might be gathered from the location; but it is not necessarily shaped by the location. This takes me back to my original point about the database designer. There is a difference between centralized “projection” and decentralized “articulation.” When the head office has ownership over the narrative, the unique aspects of phenomena associated with any location might never be conveyed. Consequently, there is apriority in meaning, ontology, and therefore data, entrenched in the organization. What it has is what it sought to gain: its data is a product of projection. In a narrative, it is not necessary to construct the data-gathering beforehand: one need not know what to collect before doing research. As such, the narrative data might be described as the articulation of phenomena, extending from the site of the data itself rather than from the predefined constructs of managers and analyst.

Imagine being told about a problem at a particular facility. You, the reader, have been given instructions to create a questionnaire to determine the nature of the problem so that a strategy can be devised to correct it. Please take a moment to form the survey now. “I don’t know anything about the problem. How can I possibly create a questionnaire?” A survey is used to gather data. Yet a person needs to have some sense of the data in order to collect it. Indeed, a person needs to already understand that a problem exists, that it likely exists in a certain way, and that certain data might be useful towards resolving the problem. The task isn’t too onerous if the researcher already knows the solution. If sales are slumping at a particular store, associates might tell customers, “We would like to ask you some questions about your shopping experience if you have a few moments.” The associates go through a list of questions none of which are necessarily relevant to the decline in sales but which seemed to make sense during the design of the survey. “Did you find what you are looking for? Did you have difficulty asking for assistance? Did you make use of the restroom? How do you feel about the price? How is the quality?”

“We would like to know about shopping experience. Would you be willing to share some of your stories with us?” The client responds, “Well, where should I start?” “Please feel free to start anywhere you like,” says the associate. The client might go through a lengthy story indeed. I can’t say exactly where such a story might go. However, wherever it goes, it is because the client wishes to travel there. The personal narrative is about allowing the client to shape his or her involvement. It is a form of social empowerment and expression. How is it possible to deal with a completely open-ended question? Based on my own experiences with conventional surveys having specific questions and limited responses options, I would say that this is nearly impossible. With codified narrative, it isn’t difficult at all, since by intent and design there are no limits to expression.

Spatial geography might be relevant in relation to personal narrative. For example, I am surprised by the amount of strategy that goes towards our selection of retailers – for me, in order to save time and gasoline. I also have a preference in terms of treatment. However, setting such matters aside, there are conversations dealing with separation, location, and positioning that to me are geographic in a perceived sense but not necessarily spatial in a physical sense. Space isn’t just space. It is the medium through which people connect and disconnect. For example, to be in an apartment where one does not know the language of the people outside is really to be confined and isolated. To move through life but not exercise any personal autonomy is to be hauled like cargo and treated like a commodity. Space is merely part of the input that we receive as we live in our brains, like watching a movie.

I once had a colleague complain about being overwhelmed about the amount of email he seemed to be receiving – maybe because he was reading everything quite carefully. Similarly when I miss a ramp while driving, despite my lack of direction, I nonetheless try to reason out how to compensate for my oversight essentially by making educated guesses. A person can feel lost in a physical space. But people routinely feel lost in their thoughts for example in relation to the paths they have taken, such as when a student is unclear about academic directions. Which is worst – living in a remote community or the sense of having being abandoned and discarded? The fact that the latter can be socially constructed does not alter how the former may have led to the feeling and enabled its persistence. It is therefore important to follow the interaction between the geography of the source and the different geographies of conversation. Accordingly, the geographic codification of narrative takes place at the level of source and conversation. Were the narrative only about physical space, I would note the literal source of the data.

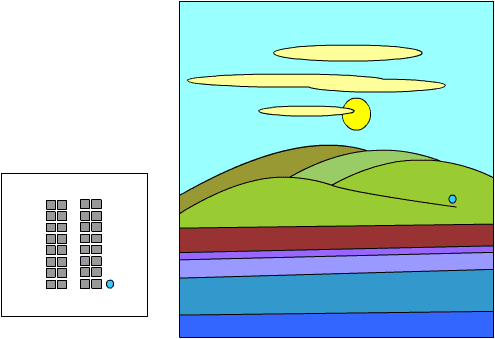

Indistinguishable by Numbers at the Most Intersects

Habitat collision and incursion might be studied by a naturalist or environmentalist: e.g. the expansion of urban populations into formerly agrarian spaces. I consider it a worthwhile lens to study the differences of people despite their apparent quantitative similarities. Speaking with a person returning from vacation, I observed that it must be shocking to come from a place of scenic beauty and a life of pleasure and freedom to an office full of cubicles where people stare at their monitors all day in order to perform certain predefined tasks. I drew a little picture of these contrasting environments below where the turquoise dot represents this individual. Think of the left image as a view from the ceiling, by the way. Human life is full of function, and we perform many routine tasks. Our environments shape the nature of our interactions with the world and therefore the metrics that we generate from our behaviours. These are metrics usually not of “performance” but rather “interaction.” I suspect that after some period of conditioning, almost everyone can interact in a manner that can lead to their quantitative similarity or at times their indistinguishability.

Many can “conform” – just enough to “perform.” As such, a person such a terrorist or serial killer can pass as “normal” considering most metrics that we gather and the capabilities of the equipment and processes for gathering. Similarly, some people might have conditions that don’t necessarily materialize in their work. I know that there tends to be sharp reactions to measurable non-conformity – as if people were much the same at the outset. My point here is that numbers have a place in order to measure certain aspects of production – but not really to understand people. (Even production doesn’t say a great deal. A company that conforms to certain prescribed production requirements is not necessarily much better off than any other. Employees at an automotive plant can produce cars at a loss and which nobody wishes to buy.) A quantitative regime sprawling with metrics barely tells researchers about organizations and people. There is an entirely different form of data that can be captured.

Inside the mind, it seems doubtful that people separate things spatially in a literal sense; but rather the separations occur by their importance to the person. I don’t mean “important” as in a coherent prioritization scheme but rather as reference points for our thoughts and decisions. The paths that we take inside are no less relevant than those that exist in the physical world that we choose to take outside. Now, this might all seem rather psychological, and perhaps on a certain level it is. But actually the transposition between physical and non-physical constructs is immensely data related. There are settings. Then there are stories that emerge from those setting; and these stories interact with the world as they unfold. However, physical actions in a physical world lead to metrics. So much of reality lives outside of the metrics – invisible to numbers. The invisible universe can be detected through our use of narrative – systematically evaluated once it is codified. Each person has a different universe. It is in constant motion and collision. It might collide in silence.

Paths that People Take

A study of narrative is a study of settings, paths, behaviours, and directions. Although physical geography doesn’t necessarily have to be involved, the narrative of a person routinely interacts with the surrounding physical and spatial environments. From my perspective, returning to my example of missing people, a database of public responses should be configured around geographic codified narrative at the outset. This is because the intersections of paths occur at a geographic narrative level rather than production. It would be terrible if the data were retained in some kind of primitive relational construct. Studying the paths that people follow whether spatial or non-spatial is a coherent approach to predict their future decisions and directions. Asserting their behaviours by virtue of superficial characteristics and by extension their placement in a statistical distribution strikes me as a crude and primitive science. My rather radical perspective is to accept data that might be entwined in social constructs: e.g. an opinion about where a person might be is not necessarily any less useful than an apparent sighting. The concept of statistical bias by populating a database with poor data is not really applicable to narrative – unless a person intends to treat codified narrative statistically. A path is not any less meaningful if few people take it – or even if a person has only heard of others thinking about taking it.

The recent terrorist bombings in Belgium are spatially significant. The incidents can be easily expressed as narrative. Would the use of codified narrative and a study of narrative paths have led to any kind of prediction? Authorities seem to have little difficulty with “reverse narrative” – going backwards to explain how events unfolded. So great is their ability to piece together the narrative after the fact, it seems incredible that the attacks occurred. I suggest that it might be unrealistic to screen luggage even before the check-in process. To me although I have an untrained eye, those being blamed for the bombings didn’t seem out of place. There were no obvious signs or markers. This brings me back to a drawing that I added to a blog in 2014 called the “Parable of the Stormtrooper and the Airstrip.” Here it is once again, posted below. My point in the picture is that a problem sometimes isn’t due to a failure of “projection” – that is to say, a failure to implement controls and a monitoring regime. Rather, the problem might be related to ineffective articulation.

Where quantitative analysis is about externally imposing an ontological regime reducing people to numbers, the codified narrative is about inclusion and participation: giving people the opportunity to shape their own stories thereby defining themselves in the broader social narrative. Society as we know it is designed to deal with people “from a distance” as numbers. The joy of studying paths is trying to understand people and being sensitive – as a society should be. One studies the paths that people take. At times these paths are physically expressed as spatial and temporal phenomena. Sometimes the paths lurk inside the person as an inward response to something external. But one need not be limited to examining the perpetrators after the fact – at the conclusion of the story. We can study where people are from, the paths they are taking, and where they are going. It is doubtful that I am the first person to suggest so. But I recommend the use of geographic codified narrative for systematic evaluation, which like quantitative analysis remains a database-oriented approach. At the same time, one cannot selectively focus on a few threatening individuals – or label people, a priori. Society has to care about what happens to each and every person – to be interested in helping to shape their successful narratives. Perhaps a great threat to terrorism is successful social integration through adaptations in society. A threat to society – when paths and intersections don’t matter – is quantitative alienation through controls over the individual.