Here are a few challenges for the mathematically inclined – most data scientists are. This is just fun problems if you have some time to kill. The first problem is about seasons in binary star planetary systems: it has implications on whether such planets are inhabitable. It is also related to time series with double periodicity. The next problems are related to infinite products, with an emphasis on building a prime-generating or at least prime-detection function. Large prime numbers are involved in many data encryption systems.

1. Seasons in Binary Star Planetary Systems

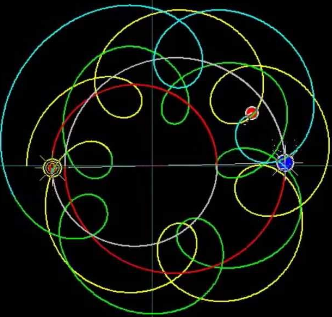

The video below shows the chaotic orbit of a planet “circling” around two stars. In this context, the concept of “year” may not even make sense. But if the two parent stars are close to each other, and the planet far enough from the two parent stars, things get less complicated. The planet could be locked to the star system (as the moon is locked to the Earth), always showing the same face) in which case there is no season. If the planet’s axis of “rotation” is tilted (like on Earth) but the tilt is the same with respect to both stars, it will face seasons quite similar to Earth. But what if the tilt is different with respect to each star – say with an angle a with respect to star A, and an angle b with respect to star B? Is this even possible? Not if the two stars and the planet’s orbit lie in a same plane.

But assuming we have two different tilts, what would be result? What if the ratio a/b is a rational number, as opposed to an irrational number?

Orbit of a planet in a binary star system

Related articles:

2. Infinite Products

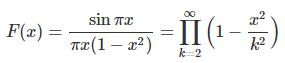

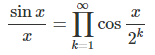

There is a famous infinite product for the sinus function: it is like factoring a polynomial of infinite degree whose roots are the roots of sin(x). It yields the following formula:

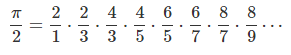

For x = 1/2, it yields the famous Wallis formula (infinite product) for the number p:

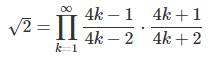

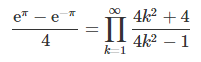

And the ratio F(1/4) / F(1/2) yields the following formula:

The above product for SQRT(2) is easy to obtain, yet I have never seen it mentioned in the literature. Maybe I do not read the right publications. For those who are familiar with complex numbers, using x = i (the imaginary unit) and multiplying by the above Wallis identity, one gets

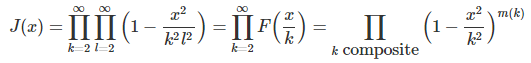

However here, we are interested in using this framework to build a continuous function that generates the prime numbers. This function, if it exists, has no practical value because it has a large number of minima and maxima, and even though it is continuous, it is anything but smooth. First, let’s define J(x) as follows:

The last product is over all positive composite (non-prime) numbers, with m(k) being the number of ways (the order matters) that k can be written as a product of two positive numbers (excluding 1 and k itself): For instance, m(60) = 10, and m(49) = 1. Now the question is whether the double product converges, or not. If it does not, we have to replace the infinite products by finite products and see the limiting behavior to adjust the definition of J, R (see below) and/or F, accordingly.

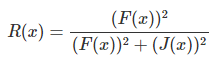

The interesting fact is that the function R(x) defined below (after potential adjustment for convergence) always takes a value between 0 and 1: It is equal to zero if and only if x is a prime; it is equal to 1 if and only if x is a composite number not the square of a prime.

Now, testing if x is a prime amounts to testing whether R(x) = 0 (or alternatively, if x is a global minimum of R.) Also, can we use R to iteratively find the prime number closest to x, for a pre-specified x?

Before answering these questions, addressing the convergence issue is critical, and if we don’t have convergence, we must find a work around.

Another interesting infinite product

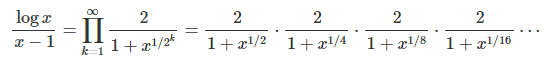

This is not related to prime numbers. I found it on Stackexchange when doing some research on infinite products. However I really like it, and I could not find it in any scientific paper, so I decided to share it with you. It has a relatively fast convergence to compute logarithms. A simple proof of this result can be found here.

When x = 2, the first 15 factors provide an approximation to log(2) that has five correct digits. Finally, a similar argument, using successive applications of the formula sin 2x = 2 sin x cos x, yields the well known identity

When x = p/2, it provides an interesting and well known infinite product for the number 1/p.

Related articles:

- Number theory — See Prime Number Generating Function in section 4

- Infinite products

- A Beautiful Probability Theorem

- 88 percent of all integers have a factor under 100

- Formula generating digits of square root numbers

DSC Resources

- Services: Hire a Data Scientist | Search DSC | Classifieds | Find a Job

- Contributors: Post a Blog | Ask a Question

- Follow us: @DataScienceCtrl | @AnalyticBridge

Popular Articles