Bernoulli trials are random experiments with two possible outcomes: “yes” and “no” (in the case of polls), “success” and “failure” (in the case of gambling or clinical trials). The trials are independent from each other: for instance tossing a coin multiple times, or testing the success of a new drug against a specific medical condition, on multiple patients: improvements for a specific patient is viewed as a success, lack of improvement as a failure.

Here we are interested in maximum runs of successes (also called record runs), when they are expected to occur, and their expected length or duration. While the classical application is in games of chance, we will discuss an exciting application in number theory, more specifically, very good approximations of irrational numbers by rational numbers, and numeration systems with a non-integer base. We will also consider the case where the trials are not independent, and where there are more than two outcomes. For instance, if throwing a dice rather than a coin, there are six rather than two outcomes.

The data used here is simulated and allows us to get some good approximations for a number of interesting statistics. It is based on an unusual pseudo-random number generator that is very relevant to the problem being studied. A more theoretical approach can be found here, with connections to extreme value theory and the Gumbel distribution. See also my previous article Distribution of Arrival Times for Extreme Events, posted here.

1. Simulations and theoretical results

Bernoulli trials with b potential outcomes, each with the same probability of occurring, can be simulated using the following system. Start with some irrational number x0 in [0, 1], say x0 = log 2 (called the seed), and use the following iterations:

an = INT(b xn)

xn+1 = b xn – INT(b xn).

INT represents the integer part function. The result of the n-th trial is an: it is a coding integer between 0 and b – 1 inclusive, representing for instance the result of throwing a dice with b sides labeled 0, …, b – 1. Also, an is the n-th digit of x0 in base b. These digits are strongly conjectured to be independent from each other, and have the same probability 1 / b to take on any of the b potential values. Thus this scheme can be used to simulate the Bernoulli trials in question. Also, unlike traditional pseudorandom number generators, it does not produce periodic sequences. Such a system can be viewed as a chaotic dynamical system, just like the sine map discussed in my previous article, here.

The Bernoulli trials generated with x0, that is the sequence a0, a1, and so on, constitutes just one instance of a Bernoulli experiment. If you try with N different seeds (the number x0), then you end up with N different, independent instances of Bernoulli experiments sharing the same dynamics, and things start to become interesting.

1.1. Simulations

I performed N = 200 simulations, each representing a Bernoulli experiment starting with a different seed x0 each time, each consisting of 1,000,000 trials, with b = 3. Possible outcomes of each trial are 0, 1 or 2. I looked at successive record runs of zeros. For one of these experiments (a typical case), I’ve found this:

- One isolated zero (the first occurrence of zero) starts at position n = 3

- The first run of 2 zeros starts at position 13 in the digits expansion

- The next longer run consists of 3 zeros, starting at position 69

- The next longer one (4 zeros) starts at position 132

- Then we have 5 zeros starting at position 670, then 6 starting at position 743, 8 starting at position 13411, 10 starting at position 58454, and 12 starting at position 384100.

The observations can be summarized by the following bivariate sequence:

(3,1), (13,2), (69,3), (132,4), (670,5), (743,6), (13411,8), (58454,10), (384100,12), …

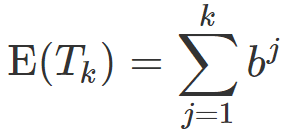

If you blend all the sequences of vectors (X, Y) together, from the 200 experiments, you get the following:

Figure 1: Record runs of Y zeros vs the position X at which they occur in a Bernoulli experiment

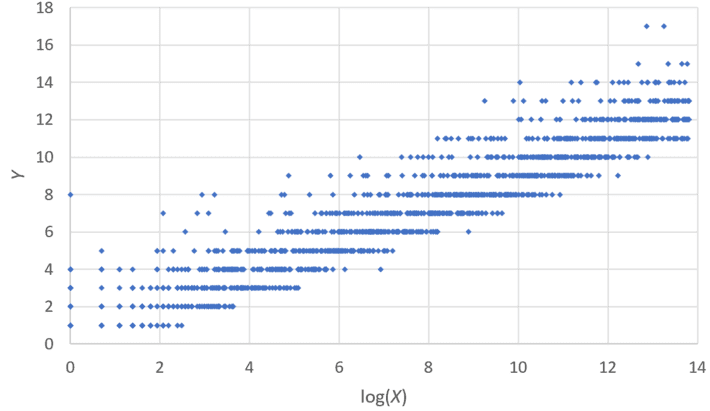

Note that in Figure 1, the plot represents Y versus log(X), and b = 3. A record run equal to Y means that starting at position X, we observe the first instance of a (record) run consisting of Y consecutive zeros, in at least one of the N experiments. In Figure 2 featuring aggregated data, you can see the average log(X) computed across the N = 200 experiments, for any record run of length Y = 0, 1, 2, and so on (up to Y = 13). The chart speaks for itself; in the linear fit in Figure 2, the slope approaches log b as N tends to infinity.

Figure 2: Same as Figure 1, with log(X) averaged across the N = 200 experiments

1.2. Theory

A lot of theoretical results are known for maximum runs. We present a few of them here, with additional references. Note that in my article, I focus on record runs, which are different from maximum runs: in any Bernoulli experiment, maximum runs correspond to the first occurrence of a run of length 2, 3, 4, and so on. Record runs, as in the example outlined at the beginning of section 1, do not necessarily increase by unit increments: in my example, the first run of length 7 (not a record) occurs after the first (record) run of length 8. In short, you see a run of length 8 before you see one of length 7.

The main theoretical results, provided by Yuval Peres, are:

- Let Rn be the length of the longest run in the first n digits. Then Rn log(b) / log(n) tends to 1 almost surely as n tends to infinity. It was first proved by Renyi, see the discussion in reference [1].

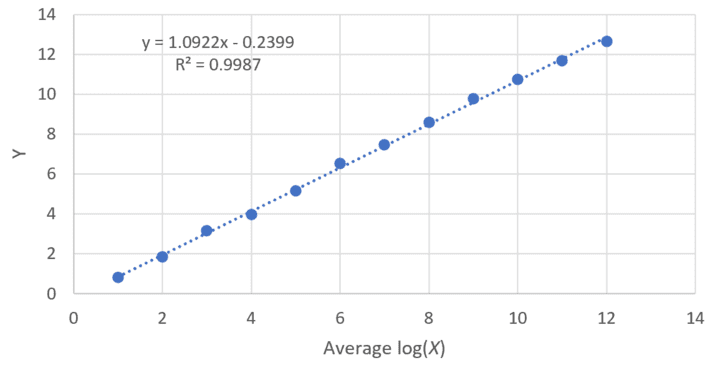

- The waiting times Tk for the occurrence of a run of length k satisfy that Tk / E(Tk) is asymptotically exponentially distributed with mean 1. See references [2] – [4]. We also have (see reference [5] and [7]):

All references are in section 3. Note that these theoretical results apply to any run, not just runs of zeros.

2. Application and generalization

If you replace the integer b by a non integer (strictly larger than 1), then the Bernoulli trials will inherit the properties of that unusual numeration system:

- The number of potential outcomes, for any trial, is INT(b), the integer part of b

- The trials are no longer independent: the n-th outcome an is correlated with an+1

- Outcomes have different probabilities: P(an = 0) is not the same as P(an = 1)

Nevertheless, once can still perform the same simulations to estimate the statistics of interest. If b is a quadratic irrational, the corresponding successive outcomes (the an‘s) follow a Markov chain model. See here for the theoretical details.

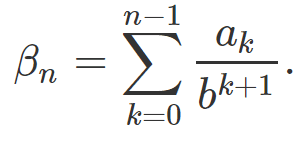

Regardless of whether b is an integer or not, the application we are interested in is the approximation of irrational numbers by a specific class of numbers. This is usually done using continued fractions if the class of numbers in question consists of the rational numbers, and there is an abundant literature on this topic, see for instance here. However, we focus instead on best approximations of an irrational number x0 in [0, 1] by a rational number βn, where

Note that βn can be expressed as pn / qn, a quotient of two integers if b is an integer, with qn being equal to b at the power n. The best approximation is obtained when the ak‘s are the successive outcomes of the Bernoulli experiment with seed x0, or in other words, the first n digits of x0 in base b. The approximation is exceptionally good if the last digit an-1 is not zero, and it is followed ty a record run of digits equal to zero. The length of that run is expected to be asymptotically of the order to (log n) / (log b). It can not be better than that, for a fixed n. Therefore, I propose the following conjecture, based on the probability distributions associated with extreme (record) runs discussed in section 1.

Conjecture

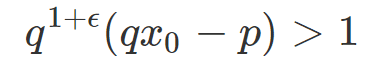

For most numbers x0 in [0, 1], and for any ε > 0, if p / q is an approximation of x0, with p, q co-prime positive integers, we have

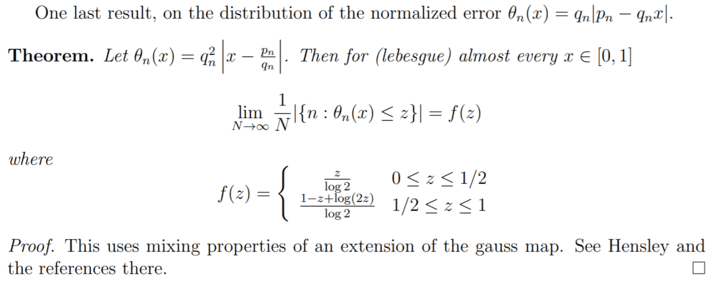

The details as how I came to this conjecture are outlined in the section Connection with approximations of irrationals by rational numbers, in this article. While this is beyond the scope of this article, a discussion of best approximations by continued fractions leads to a similar conclusion. In particular, if pn / qn is the n-th convergent of the number x, we have the following result, see last theorem in this article, pictured below. In short, it says that if ε = 0, then only some proportion of all numbers x0 will satisfy the above inequality. With ε > 0, almost all x0 will.

Finally, record runs in Bernoulli trials is a topic of combinatorial analysis, and thus relevant to machine learning, with numerous applications in combinatorics. Also, you can learn more about non-integer bases in this article. A summary table is available here.

3. References

[1] Schilling, Mark F. The longest run of heads. The College Mathematics Journal 21, no. 3 (1990): 196-207.

[2] Aldous, David. Probability approximations via the Poisson clumping heuristic. Vol. 77. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

[3] Földes, A. The limit distribution of the length of the longest head-run. Period Math Hung 10, 301–310

[4] Godbole, Anant P. Poisson approximations for runs and patterns of rare events. Advances in applied probability (1991): 851-865.

[5] Feller, William. An introduction to probability theory and its applications. 1957.

[6] Gerber, Hans U., and Shuo-Yen Robert Li. The occurrence of sequence patterns in repeated experiments and hitting times in a Markov chain. Stochastic Processes and their Applications 11, no. 1 (1981): 101-108.

[7] Li, Shuo-Yen Robert. A martingale approach to the study of occurrence of sequence patterns in repeated experiments. Annals of Probability 8, no. 6 (1980): 1171-1176.

To receive a weekly digest of our new articles, subscribe to our newsletter, here.

About the author: Vincent Granville is a data science pioneer, mathematician, book author (Wiley), patent owner, former post-doc at Cambridge University, former VC-funded executive, with 20+ years of corporate experience including CNET, NBC, Visa, Wells Fargo, Microsoft, eBay. Vincent is also self-publisher at DataShaping.com, and founded and co-founded a few start-ups, including one with a successful exit (Data Science Central acquired by Tech Target). You can access Vincent’s articles and books, here.