Tokenomics is the economy of this new world. This is a no-holds-barred, in-depth exploration of the way in which we can participate in the blockchain economy.

The following is an excerpt from the book, Tokenomics by Thomas Power and Sean Au and published by Packt.

One of the biggest challenges of playing in the ICO space is trying to understand the rules to play by. Regardless of what anyone says, we all live in a world bound by rules. We always have and always will, yet technology knows no bounds and unabatedly continuous to leap ahead, regardless of global boundaries or jurisdictions.

In the early days of ICOs, everything was experimental, but when more money poured in, and when hacks, bugs, and unscrupulous behavior started garnering worldwide media attention, the various regulatory bodies around the world started taking notice. Then, all of a sudden, the most important person in the ICO team was not the geek but the lawyer.

Security tokens and the SEC

Quite often, when security tokens are discussed, the SEC is mentioned. This is because the US Securities and Exchange Commission is an independent federal government agency responsible for protecting investors and maintaining the fair and orderly functioning of the securities markets of the largest economy in the world. So, what the SEC does matters to the rest of the world.

The goal of the Securities Act of 1933 was to remove the information discrepancies between promoters and investors. In a public distribution, the Securities Act prescribes the information investors need to make an informed investment decision, and the promoter is liable for material misstatements in the offering materials.

According to the 15 US Code § 77b (a)(1), the term security means any note, stock, bond, profit-sharing agreement, investment contract, option, transferable share, or voting-trust certificate (https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/15/77b). This is a non-exhaustive list but serves to illustrate the point of an investment contract.

What is an investment contract?

An investment contract, for the purposes of the US Securities Act, means “a contract, transaction or scheme whereby a person invests their money in a common enterprise and is led to expect profits solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party, it being immaterial whether the shares in the enterprise are evidenced by formal certificates or by nominal interests in the physical assets employed in the enterprise.” (https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/328/293/case.html#298)

In summary it:

- Is an investment of money

- Is in a common enterprise

- Has the expectation of profits

- Is derived solely from the efforts of others

Security tokens can be seen as an investment contract, where the main purpose of purchasing the token is the anticipation of future profits in the form of dividends, revenue share or, most commonly, price appreciation. These security tokens are essentially securities whose ownership is represented through a crypto asset that is registered on a blockchain.

This is important to understand because in the US, for example, any investment or purchase that is considered a security is subject to the Securities Act (http://legcounsel.house.gov/Comps/Securities%20Act%20Of%201933.pdf) and the Securities Exchange Act (http://legcounsel.house.gov/Comps/Securities%20Exchange%20Act%20Of%…), and as a result is subject to regulation and registration with the SEC.

So how does one determine what a security is? In the US, the Howey Test is employed, which was a landmark case in 1946.

The Howey Test (US-based companies)

In 1946, the Howey Company, founded by W.J. Howey, leased part of its citrus farms in Florida to finance another venture. The buyers of the land, attracted by the success of the Howey Company, invested with the expectation of profiting from its work.

Real estate contracts were offered for plots of land with citrus groves. The Howey Company offered the buyers the option of leasing the land back to it. The Howey Company would then tend to the land, harvest, and market the citrus fruits. As most of the buyers were not farmers and did not have agricultural expertise, they were happy to lease the land back to the Howey Company.

This fact suddenly made the plots of land an investment contract. The SEC moved in to block the sale and the Supreme Court, in issuing its decision, found that the Howey Company’s leaseback agreement was a form of security. This was then developed into a test to allow anyone going forward to determine if certain transactions are investment contracts. If they are, they will then be subjected to securities registration requirements.

The Howey Test started a new era of defining securities by focusing on their substance, rather than their form. Simply labeling a token as a “utility” does not change the substance of a white paper. No matter how many times the word “utility” is used, it may very well still be a security under US law if it passes the Howey Test. This is why it became a common practice for the courts to review the economic realities behind an investment scheme, disregarding its name or form.

There are also others tests such as the Risk Capital Test (http://thestartuplawblog.com/token-sales-risk-capital-test/) and the Family Resemblance Test, (https://www.compliancebuilding.com/2012/05/31/is-a-note-a-security/), among others, but the Howey Test is currently the most commonly referred to.

US citizens

The reason that all of this is important is that the token issuer can be prosecuted for running a non-compliant ICO (according to the US Securities Act) if it allows US citizens to participate. The token issuer doesn’t even have to reside in the US or be registered in its territories as a company. Even if the company is registered outside of US jurisdiction, if it allows US citizens to participate in its ICO then it’s automatically violating the federal law.

This is why many projects often decide to avoid the sale of their tokens to US-based users. It is not that the project doesn’t want US investors, it just doesn’t want to deal with the headache of supplying investor background data to the government in the future.

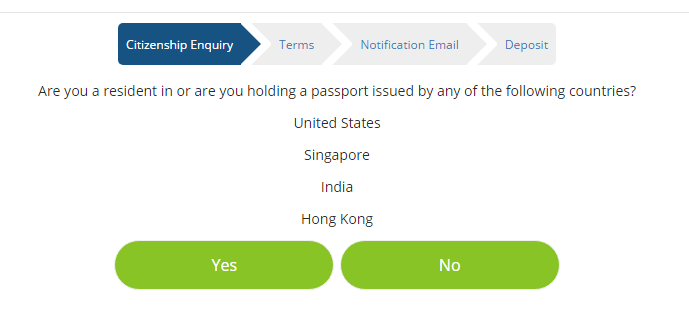

The Monaco ICO asked if the user was a resident of, or holding a passport of, a list of countries. If the answer was yes, an apology page would appear preventing the user from continuing:

Figure 1: The Monaco ICO page citizenship enquiry

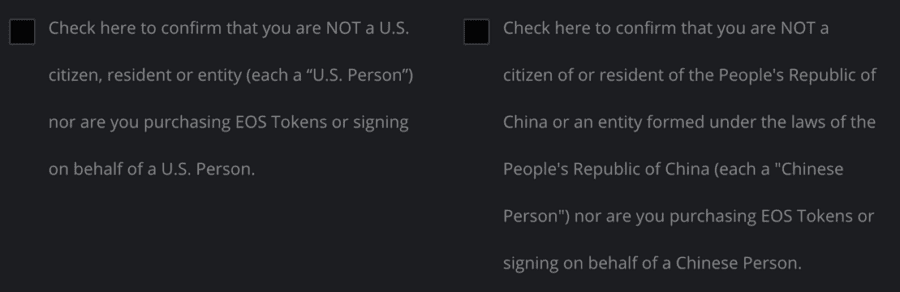

EOS provided two tick boxes asking users to confirm that they were not a citizen or a resident of the US or China. Some ICOs, particularly in the early days, did not do any further checks, but others did ask for further identification documents, such as a driving license or passport details, to be uploaded.

Figure 2: The EOS token sale page

Cobinhood asked users if they were a citizen of various countries that they deemed high risk in a legal sense and if so, the website redirected them to a “thank you for your interest but you cannot participate in the ICO” page. Cobinhood explained this decision:

While most participants of any citizenship can join the ICO, unfortunately, we are unable to accept participation from citizens of the United States of America, Canada, China, and Taiwan due to existing regulations in their respective states. (https://web.archive.org/web/20180315112347/https://cobinhood.zendes…)

Many of the organizations conducting an ICO have been desperately trying to avoid having their tokens classified as securities. Being classified as a security automatically comes with many regulations and limitations, no matter what the country in question is, such as who can invest in these tokens and how they can be exchanged.

Secondary trading and liquidity are also greatly reduced for these kinds of tokens, as securities cannot be traded freely and are subject to many restrictions. In fact, crypto exchanges do their own due diligence to avoid listing security tokens if they are not licensed to do so. This can limit or even destroy the network effects and the use of the tokens to build a widely adopted platform or protocol. Securities laws are complex and often confusing. Terms such as “common enterprise” are imperfectly defined and different courts may apply different tests for determining whether an investment is a security or not.

In the US, and in fact in many developed countries around the world, securities are heavily regulated and selling unregistered securities can result in significant fines and prison sentences. We also know that there are significant costs and efforts involved when complying with securities law, in order to legally accept money from investors.

AML/KYC

AML (Anti-Money Laundering) and refers to policies and legislation that forces financial institutions to proactively monitor their clients in order to prevent money laundering and corruption. These laws require financial institutions to report any financial crimes they find and do everything possible to stop them.

KYC (Know Your Customer) and it is the process of a business identifying and verifying the identity of its clients. The main objective of this policy is to prevent money laundering, identity theft, terrorist financing, and financial frauds. Identifying contributors and complying with AML regulations is almost a necessity now for any ICO.

The most famous case of a self-imposed retrospective AML/KYC was Tezos. On June 10, 2018 the Tezos Foundation announced a KYC/AML requirement for all contributors, almost a year after its ICO:

“As the operational details for the Tezos betanet launch continue to be finalized, the Tezos Foundation would like to announce the implementation, at this time, of Know Your Customer/Anti-Money Laundering (KYC/AML) checks for contributors.” (http://tezosfoundation.ch/news/tezos-foundation-announces-kyc-aml/)

The Tezos Foundation determined that this was the best way forward to avoid any future compliance complications. The Foundation reasoned that due to a maturing of the blockchain ecosystem in the 10 months since it did its ICO, KYC, and AML requirements had become standard practice, so Tezos wanted to retrospectively comply as well.

The announcement was met with some backlash online that renewed claims that Tezos was a scam, in conjunction with the infighting and the multiple delays of the platform.

SEC statements

On June 6, 2018, Jay Clayton, the Chairman of the SEC, announced that the SEC will not change securities law to cater to cryptocurrencies:

Cryptocurrencies that replace the dollar, the euro and the yen with bitcoin, that type of currency is not a security. However, a token or a digital asset, where I give you my money and you go off and make a venture, and in return for giving you my money I say “you can get a return” that is a security and we regulate that. We regulate the offering of that security and regulate the trading of that security. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wFr1ooaVPjY)

On June 14, 2018, William Hinman, the director of the Division of Corporation Finance at the SEC, gave a speech at the Yahoo All Markets Summit: Crypto conference in San Francisco and stated that Bitcoin and Ether are not securities:

Applying the disclosure regime of the federal securities laws to the offer and resale of Bitcoin would seem to add little value. And putting aside the fundraising that accompanied the creation of Ether, based on my understanding of the present state of Ether, the Ethereum network and its decentralized structure, current offers and sales of Ether are not securities transactions. (https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/speech-hinman-061418)

The key is that Hinman’s analysis of whether something is a security or not is not set in stone. Digital assets that have utility can be sold as an investment strategy that could later be deemed to be a security. Then, as the network develops to the case where there is no longer any central enterprise being invested in, it can be deemed as not a security.

The key is around decentralization. If the network is sufficiently decentralized, the asset may not represent an investment contract because the ability to identify an issuer or promoter to make the required disclosures becomes difficult and less meaningful.

Summary

When ICOs burst onto the scene, no one could have predicted how large the legal ramifications would be. For those that did, they either tried to ignore it and fly under the radar or got in fast in order to minimize retrospective effects. The challenge is that while every ICO claims utility, many business models are designed to increase utility in order to drive up demand and thus the value or price of the token. With this increase in value, many have the expectation of profits.

In this article, we learned what a security is from the eyes of the SEC and looked at the Howey landmark case when determining if something is an investment contract or not from a US perspective. The global regulatory stance of various countries was discussed, where, in general, other than the outright ban from China and South Korea, regulators are open to working with businesses within a framework in an attempt to not stifle innovation.

The SEC started sending signals in the latter half of 2017 and its reports into The DAO and the Munchee ICOs provide intriguing insights into the ICO world from the side of the regulators. This should not serve as a negative deterrent but as a signal to be sensible and compliant and if uncertain, to seek professional advice. The evolution of white papers then showed more and more legal clauses being included to protect the ICOs and their founders.

You have just read an excerpt from the book, Tokenomics by Thomas Power and Sean Au and published by Packt.

The author gives an unbiased, authoritative picture of the current playing field, exploring the token opportunities and provides a unique insight into the developing world of this tokenized economy.