As the Omicron variant of Covid-19 surged around the globe in 2021, managers who had begun contingency plans for a return to the office quietly shelved them to wait out the next wave. Heading into the summer of 2022, the omicron-delta variant lurks on the horizon, though whether or not this will trigger the massive hospitalization wave of the previous version remains to be seen. That health officials seem to be saying that it’s time to treat the pandemic as having reached an endemic stage may be wishful thinking, but executives at many companies are taking this as an indication that they need to start getting people to return to the office.

There now seems to be two distinct camps emerging – the first advocating that Work From Home (WFH) has proven itself as a viable way of working and should be adopted as universally as possible – is made up, not surprisingly, by many workers and labor advocates. The advantages there are well known – WFH generally makes for a happier workforce as people control their own time, do not need to spend countless hours commuting, are better able to concentrate on projects with the need for fewer meetings, don’t have to spend as much time on appearances, and so forth.

Those advocating for a Return to the Office (RTO), on the other hand, have a variety of reasons for bringing the workforce back into corporate walls. Some of these are publicly stated; others mask concerns that may be more of an indictment on corporate work than they want to publicly admit. These will be explored in this editorial.

The Lack of Collaboration of WFH

Take a look at stock photos of corporate life and what you see are pictures of (mostly young) people scattered around a table, throwing out ideas in brainstorming sessions that are then captured via whiteboards. This is typically augmented with the watercooler session, where two people bump into one another at the water cooler, have a fast-paced discussion that sparks new ideas, then off each goes to their respective cubicles, now inspired to create the next marketing masterpiece.

Ironically, it’s worth noting that in both cases, these collaboration efforts generally occur not when management is present but when it’s absent. The watercooler has largely been replaced by the coffee shop located off company premises, where people go when they want to get away from corporate oversight or just need to get away from their cubicles. The whiteboard has been replaced with Miro boards, collaborative documents (and code environments), content management systems, and dozens of other tools that provide collaboration with less pressure than the loudest person in the room factor that tends to dominate such sessions.

Indeed, in many respects, collaboration has improved in the WFH environment partly because it has given those who would otherwise not have a voice in these conversations a means to express their own opinions and partly because it is now easier to record these collaboration efforts, making them more persistent than a snapshot of a whiteboard someone took promising to transcribe it and never following through. Similarly, the ability to meet off-premises can be facilitated by a zoom call or, if people are nearby, can be held as an informal lunch or Starbucks closer to home where the fear of a manager coming in is far lower.

The Cost Savings of Corporate Environments

An argument frequently made about RTO is that it is generally more energy-friendly to bring people together to work than having the extra costs of high-speed internet distributed to residential households. There has been very little evidence that one is more energy-efficient than the other, but a few counters are worth noting. The cost of computing by individual workers will be the same regardless – the laptop is either drawing from the urban or the residential grid. Most people working from home generally do not keep the house lit during the day (while corporate offices are always lit), and usually, people do not keep their houses at the near ice-box levels that are the norm for most offices.

Internet access in this day and age has shifted to the residential side due to one reason: streaming. Ordinarily, business Internet has tended to get the lion’s share of the attention of Internet bandwidth, but with streaming, this has shifted dramatically in favor of home-workers. The growth of wireless routers has only exacerbated that trend to the extent that the quality of the Internet signal going into homes is frequently superior to what’s available from work. Yes, this has added some to the energy consumption of households, but there’s one elephant in the room: the commute.

The commute is a business expense pushed primarily onto workers and municipalities. To commute, you either need a car, or you need to have access to transit services that are under increasing pressure from small-government advocates. You need to allocate hours to get to and from work, often creeping along at five miles an hour due to traffic jams. You need to supply gas to that car at inflated prices as gas becomes hostage to geopolitical factors outside your control. In other words, removing the commute removes one need for having a vehicle, slows the need for infrastructure development, cuts down significantly on air pollution, and makes up for any gains in consolidating workers.

The Need for Business Culture and Social Interaction

While similar to the issue of collaboration, fostering business culture and social interaction is frequently cited by advocates of RTO. The problem is that business culture is a nebulous concept involving pride of association, expected codes of conduct, and shared history. Every CEO wants to believe that their corporate culture is a shining beacon, but most workers have a far less idealized version of the company they work for in their head, one involving abusive managers, arbitrary layoffs, death marches to failed projects, inane company activities, and stratification of not just responsibility but rewards.

Not surprisingly, given the opportunity to escape companies that prize their corporate culture for senior management but do almost nothing for the 95% of the company that is engaged in making the company function, many workers are taking advantage of work from home to regain some of their own culture and social interaction. They are spending more time interacting with their children’s schools, gaining new hobbies, interacting with book clubs, sports clubs, or other interest groups, focusing on their religious beliefs and community cultures, and meeting people for dinner, drinks (of the alcoholic or caffeinated type), and music. In other words, they are rediscovering the culture outside of business, something that is important to them but is often seen as a distraction from work by their corporate masters.

Put another way, too many managers want the company to be the ultimate focus for their workers, and enclosing them inside corporate walls was one way to accomplish this. Break down those corporate walls, and you end up with more rounded people but less likely to be completely committed to your company (or at least the thinking seems to be, though again, anecdotal evidence suggests that too much of a commitment to any single focus or culture is counterproductive for everyone concerned).

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

Companies have invested heavily in offices, taking on long-term leases for housing their workers, and WFH abnegates that investment, leading to expensive offices that are mostly empty. This could cause those businesses to fail. It also hurts those businesses clustered around these office buildings.

This argument is weak on so many fronts that it’s hard to take seriously. About twenty years ago, several companies, primarily in the tech sector, began to experiment with virtual companies – companies that existed just of people and soft assets, not real estate. Originally, it was not easygoing because the infrastructure at the time was barely in place to support the experiment, but these companies persevered and managed to transition over to purely virtual over time with few regrets.

The Pandemic forced the second wave of virtualization in which companies that hadn’t gone virtual in the first stage had to scramble to deal with the various lockdowns. Many companies dragged their feet there, expecting that the problems inherent with the Pandemic would resolve quickly, so they saw the transition as being temporary, while those who suspected the Pandemic would hold on for a while divested much of their physical holdings. Commercial Real Estate companies also invested in switching over at least some of their properties from sole Commercial to mixed Commercial/Residential, which alleviates some of the housing shortage due to the Pandemic and provides a convenient out for companies who wish to downsize.

This is a gamble that investors have to make, not workers: hold on to mostly empty commercial real estate for some time (possibly a decade or more) or free up some of that real estate while facilitating a more open strategy.

The Power and Danger of Geofencing

Until comparatively recently, the notion of geofencing was one that most people, even those interested in labor issues, remained mostly ignorant of. Geofencing refers to the fact that workers were usually bound to remain within a commute’s distance away from their place of work. Geofencing meant that the opportunities open to workers were usually limited to those companies near which they lived, which, in turn, meant that the projects, compensation, and work patterns were closely tied to those companies. These workers were fenced in by geography, and going to work for a competitor was often an expensive proposition that involved either high relocation costs or staying within a consensus compensation range.

The Pandemic forced workers to re-evaluate how they interacted with potential employers. If you could work from home for a company half an hour away, you could work from home for a company halfway across the country. In effect, workers could reach out to new employers and were no longer as constrained to be within a commuting radius. Workers no longer were bound to a physical place and could market themselves to a much broader audience, increasing what they could be making and taking opportunities that might be otherwise locked out with their current employer.

For companies looking for fresh talent, this was a gold mine. For companies that had used much the same kind of arbitrage in outsourcing, this likely came as a shock because, in essence, the same workers were now outsourcing their employers. This likely has been a major factor in companies wishing to bring workers back within the corporate fold – their hold on those workers is rapidly diminishing, leading to companies having to evaluate labor costs not based upon a captive geofenced market but a much more open one. While it is likely that this process will eventually reach a new equilibrium, it is not an equilibrium that companies, already shellacked with the pandemic and resultant supply chain problems, are happy with.

The Loss of Control

Ultimately, all of these factors amount to the same thing – companies are losing control of the workforce. Techniques that worked very well in the early days of the modern corporation (in the 1950s) by bringing together workers to consolidate on the cost of expensive equipment and extensive manual labor have increasingly been replaced by practices in which workers simply have no reason to be on site 9-5, Monday to Friday. A new model will likely emerge from this, where most workers remain remote, with periodic conventions or other events intended to provide face-to-face time for strategizing and socializing.

However, what has happened is that the corporation has inexorably shifted into a virtual model, one where connections are both more transient and more complex than they have been in the past. This new world may also be driving the number of older workers, especially managers, to retire early as they find that the nature of management has changed unrecognizably. It is also likely that this process will continue even after the Pandemic becomes endemic – patterns believed to be fleeting have instead become the new normal.

In Media Res,

Kurt Cagle

Community Editor,

Data Science Central

To subscribe to the DSC Newsletter, go to Data Science Central and become a member today. It’s free!

Data Science Central Editorial Calendar

DSC is looking for editorial content specifically in these areas for May 2022, with these topics having higher priority than other incoming articles.

- Autonomous Drones

- Knowledge Graphs and Modeling

- Military AI

- Cloud and GPU

- Data Agility

- Metaverse and Shared Worlds

- Astronomical AI

- Intelligent User Interfaces

- Verifiable Credentials

- Automotive 3D Printing

DSC Featured Articles

- What Personal Knowledge Graphs Have to Do with Business Alan Morrison on 26 Apr 2022

- Using Stakeholder Journey Maps to Re-invent, not Just Optimize, Your Business Processes Bill Schmarzo on 26 Apr 2022

- Data quality: What and why is it important? Indhu on 26 Apr 2022

- 2 Ways in Which Automatic Data Labeling Saves Time and Costs Costanza Tagliaferi on 26 Apr 2022

- 4 Successful Integrated Marketing Communications Examples Edward Nick on 26 Apr 2022

- No, AI won’t replace astronauts – and here’s why Stephanie Glen on 26 Apr 2022

- Smart Factory- Building Future with 5G Nikita Godse on 26 Apr 2022

- An analysis of Digital Twin Applications across industries ajitjaokar on 26 Apr 2022

- Make Sure Your Online Data Science Courses Teach These 6 Core Skills Rob Turner on 26 Apr 2022

- Healthcare App Development: Why You Should Opt for React Ryan Williamson on 26 Apr 2022

- Why Agile Often Fails and What to Do When It Happens Howard M. Wiener on 26 Apr 2022

- How to Protect Your Computer Data Edward Nick on 26 Apr 2022

- DSC Weekly Digest 4/19/2022: The Case for Personal Knowledge Graphs Kurt Cagle on 26 Apr 2022

- 18 Differences Between Good and Great Data Scientists Vincent Granville on 21 Apr 2022

- How Microsoft Power BI Revolutionizes Business Ryan Williamson on 20 Apr 2022

- How AI and ML are transforming data quality management? Indhu on 20 Apr 2022

- Agile, Agile 2 and Agility, Part II Howard M. Wiener on 20 Apr 2022

- Dark Energy, Dark Data Alan Morrison on 19 Apr 2022

- 5 Main Benefits of Distributed Cloud Computing Rumzz Bajwa on 19 Apr 2022

- Fallacy of Becoming Data-driven – Part 2: Cultural Transformation Bill Schmarzo on 18 Apr 2022

- AI and Healthcare: AI as a Triaging Tool for Healthcare ajitjaokar on 18 Apr 2022

- A Glossary of Knowledge Graph Terms Kurt Cagle on 18 Apr 2022

- Zero Trust Principles: What is Zero Trust Model? Edward Nick on 17 Apr 2022

- ML classifies gravitational-wave glitches with high accuracy Stephanie Glen on 17 Apr 2022

- Using Data Warehousing as a Service (DWaaS) To Improve Customer Experience Evan Morris on 17 Apr 2022

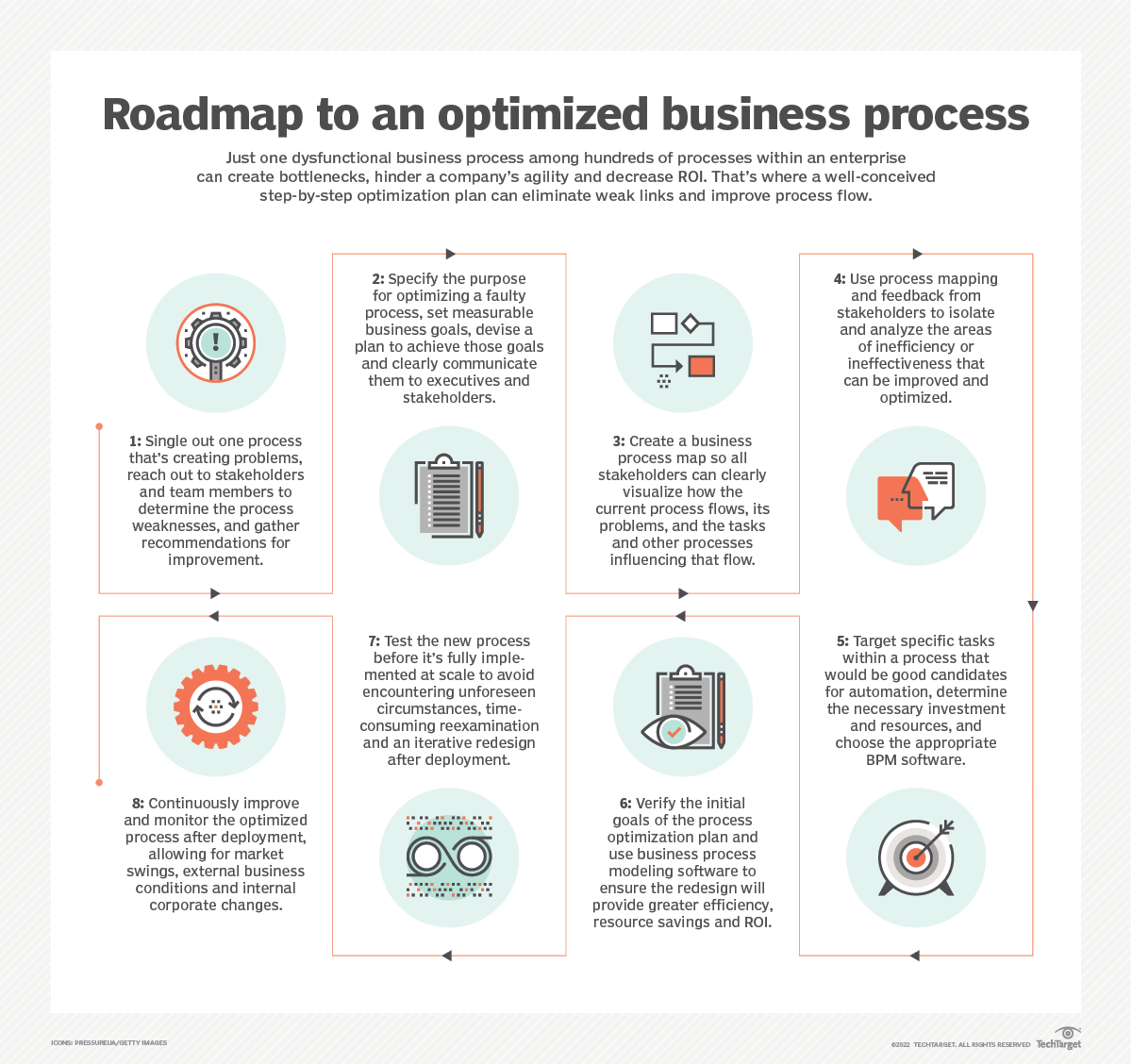

Picture of the Week