For nine years, my family and I have lived in a house in Issaquah, a little community about twenty minutes east of Seattle. The town still retains its charms — a downtown area about three blocks long that includes a vintage (and long since decommissioned) gas station, numerous restaurants, a live theater, the library, and the remnants of the Issaquah railroad station that has now become the town’s museum. The Salmon Hatchery just west of downtown is the starting point for a years-long journey to the Pacific for a variety of steelhead trout and coho salmon, and the inspiration for the Salmon Days festival when the salmon return.

This winter, the creek that the salmon follow overflowed its banks and partially submerged the surrounding neighborhood, including our house. This created a harrowing tale in which we were desperately laying down towels, blankets, and just about everything else we could to keep the water from getting too far inside, though in the end, it necessitated replacing a wooden laminate floor and a considerable amount of drywall. We and our landladies mutually agreed that it was time to move on, they to sell the house into the ridiculously hot Seattle market, us to find a place that wouldn’t leave us bailing out the dining room again.

After a couple of months of looking, we finally found a new place just a few miles away, for more than we’d planned on paying but with more space than we expected, so in the long round things balanced out. This brings up the first observation: After two years of significantly reduced construction due to the pandemic, population growth has created a distinct dearth of houses in the region and has driven up prices by 25-35%. This has made Seattle a seller’s market, exacerbated by the fact that there was a net 2.4% increase in Seattle’s population even during the pandemic.

Moreover, the core King Country area is geographically constrained by water bodies on the west side and mountains on the east side, so there is comparatively little land that hasn’t already been developed. This is becoming common in many coastal areas, especially on the West Coast, and so we in Seattle are beginning to see the same dynamics that have been a feature of real estate in Silicon Valley, where it has become too expensive for even tech people to live. This pushes the drive to higher salaries here and creates real hardship for those who don’t have the rather inflated salaries that tend to mark high-tech professions.

There’s been a long-standing assertion in economics that inflation is due to higher labor demand for wages (or due to loose monetary policy) and that as wages go up, so too does inflation. I’ve long suspected this to be bad data science. Inflation occurs when supply gets disrupted, whether due to pandemics, wars, natural disasters, or unexpected population growth, while wages generally tend to lag, rather than lead, inflation (when they correlate as well).

Reduced supply causes a rise in prices as upstream goods become harder to acquire (causing cost increases), which usually manifest as higher prices for consumers as producers pass these costs along. As supply chains begin to recover, the costs go down for the upstream producers, but prices, once they go up, tend to stay at the higher levels – partially because of contracting issues, partially out of greed as manufacturers become reluctant to lower prices because they are making more profit. This means that higher prices become baked in.

By the time goods reach consumers, the ability of those consumers (who are also workers) to pay for the goods becomes so sufficiently compromised that they are effectively priced out of the market. Ordinarily, this leads to labor pressure to raise wages which do go up, but usually not by enough to make a real difference. This has been the state of things for roughly the last twenty years, but the rise of inflation has typically been subtle enough that while real spending power dropped, it didn’t drop enough fast enough to be obvious.

What has changed is that this time around, the pandemic accelerated the time frame in which certain technologies were adopted, most notably teleconferencing, collaboration tools, and the migration to the cloud, by about eight years. Had Covid-19 not hit, we would have seen levels of remote work where they are now about 2030. One of the most significant implications of this is that the places employees could work jumped dramatically, from perhaps sixty miles to around 2500 miles for many people.

While it has been possible for digital nomads to function before, in most cases, these were primarily writers or programmers who worked independently anyway. Yet the pandemic exposed the reality that work (for many) no longer required a physical presence.

For some, it marked the end of their career, as they realized that they no longer looked forward to going into the office. For others, it meant that they could either continue working stressful jobs at low pay that ate up most of their time, or they could find work elsewhere that they could do on their own schedule. The danger of the gig economy has long been that one lost the surety of a reliable income, but the major benefit of the gig economy was that you could do more things with the time that you did have available and could more readily move to better employment situations at higher pay and less stress.

This new mobility is becoming a major problem for many employers because they are no longer just competing for talent with the other players in their field. They are now competing for the attention of that talent who may want to focus on the projects that may make them more financially independent.

This moves beyond technologists. Truck drivers have been leaving the large shipping haulers in record numbers because the wages they make (and the hours they work) are forcing them to operate at a loss. When truckers can go through independent routers (in the same manner that drivers go through Lyft or Uber), they can better optimize their own operations, allowing them to steer clear of unprofitable routes. Teachers are going into areas such as curriculum development, leaving a field that has become characterized by low pay, long hours, dangerous conditions, and micromanagement.

It is hard sometimes to realize that one is in the midst of a revolution until afterward. Barring the potential (perhaps even likely) broadening of the war in Ukraine, inflationary pressures due to the pandemic are already easing, but the new normal of remote work has only just begun to play out economically and politically. Systems are complicated because healthy ones are dynamic — change begets change. This week, Emeritus DSC Editor Vincent Granville talks about his own experiences with the labor market in The Myth of the Data Analytic Talent Shortage.

Okay, it’s time to go back to packing boxes. Hey, has anyone seen the cat? What do you mean you think we packed her?!

In media res,

Kurt Cagle

Community Editor,

Data Science Central

To subscribe to the DSC Newsletter, go to Data Science Central and become a member today. It’s free!

Data Science Central Editorial Calendar

DSC is looking for editorial content specifically in these areas for April 2022, with these topics having higher priority than other incoming articles.

- Autonomous Drones

- Knowledge Graphs and Modeling

- Military AI

- Cloud and GPU

- Data Agility

- Metaverse and Shared Worlds

- Astronomical AI

- Intelligent User Interfaces

- Verifiable Credentials

- Automotive 3D Printing

DSC Featured Articles

- Building a Data Products-centric Business Model Bill Schmarzo on 05 Apr 2022

- Data Discovery for ML Engineers German Osin on 05 Apr 2022

- Content Metrics That Can Help You To Write Dissertations EdwardNick on 05 Apr 2022

- Comparative analysis of an Intel and AMD Processor Karen Anthony on 05 Apr 2022

- AI And Its Impact On Diversity And Inclusion Aileen Scott on 05 Apr 2022

- How Data Intelligence Platforms Promote Business Success Kerry Pearce on 05 Apr 2022

- Exploring AI labeling for children’s products ajitjaokar on 05 Apr 2022

- Data Augmented Healthcare Part 2 Scott Thompson on 04 Apr 2022

- DSC Weekly Digest: Transitions and the Arc of Systems Theory Kurt Cagle on 03 Apr 2022

- A different take on business intelligence Alan Morrison on 03 Apr 2022

- Top Ways in Which AI Impacts Grocery Retail Ryan Williamson on 03 Apr 2022

- Blockchain Won’t Save The Metaverse Stephanie Glen on 03 Apr 2022

- The Myth of Analytic Talent Shortage Vincent Granville on 03 Apr 2022

- How Python Became The Language for Data Science Sonia Mathias on 30 Mar 2022

- The Increasing Importance of Master Data Management for Your Business: A Primer Rex Ahlstrom on 30 Mar 2022

- How ECash Will Change The Economy Kurt Cagle on 30 Mar 2022

- Automated Inventory Management System: An Ultimate Guide for 2022 and Beyond James Wilson on 29 Mar 2022

- What is the Difference Between Bounce Rate and Exit Rate? EdwardNick on 29 Mar 2022

- Five Major Benefits That Microsoft Power BI Brings To Data Scientists ImensoSoftware on 29 Mar 2022

- What’s Your Business Model Choice: Hammers or Casino? Bill Schmarzo on 28 Mar 2022

- Datacenter relocation is now easier, faster, and more affordable Karen Anthony on 28 Mar 2022

- The Evolution of Astronomical AI Stephanie Glen on 28 Mar 2022

- What to Do About the New AI Regulation? Andrey Koptelov on 28 Mar 2022

- How Automation and AI Are Changing Internet Marketing Rumzz Bajwa on 28 Mar 2022

- Three Critical Steps for Data-Driven Success Kerry Pearce on 28 Mar 2022

Picture of the Week

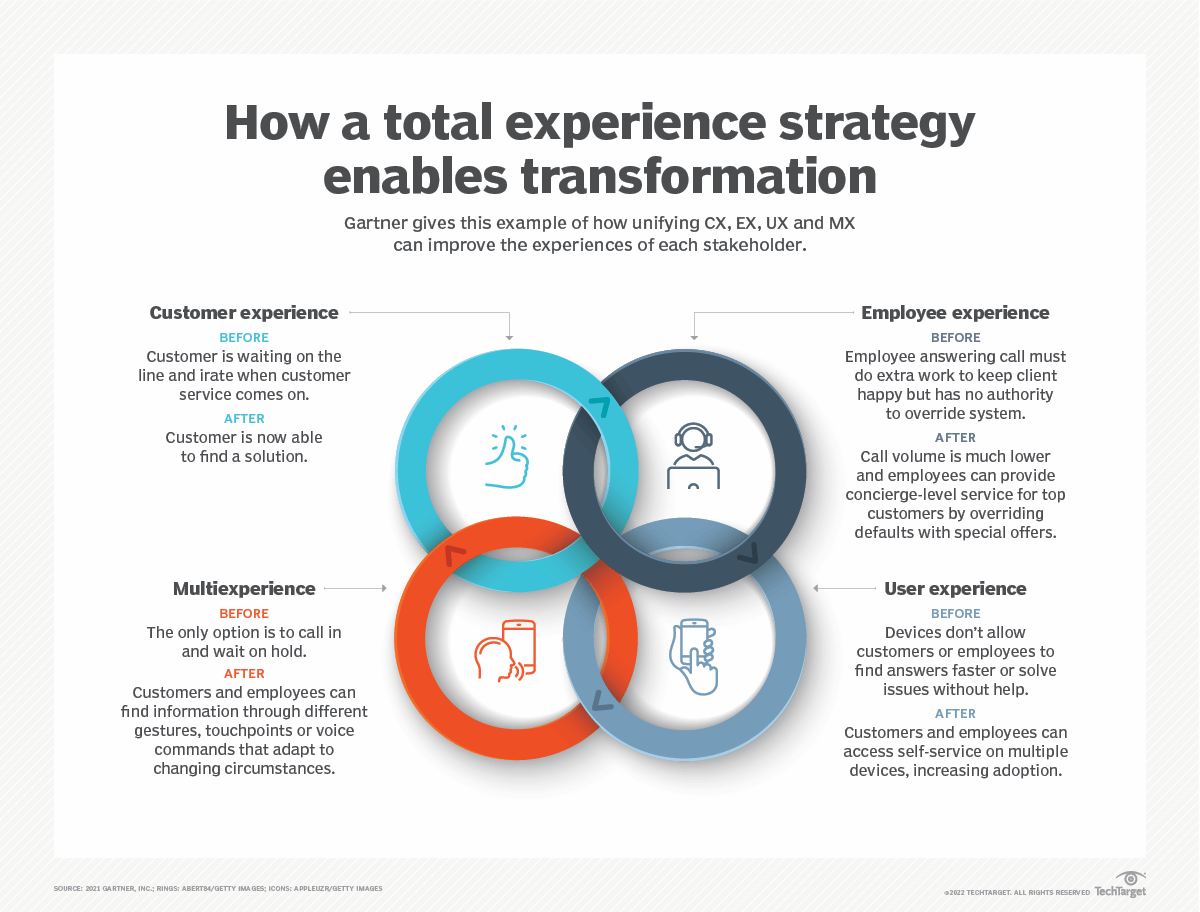

How a Total Experience Strategy Enables Transformation