Announcements

- For 40-plus years, organizations have used the language of SAS to build assets such as revenue forecasting models, customer retention models, analyze risk at enterprise levels and perform compound discovery. They are now seeking to include modern programming languages in their model building. With Altair SLC, organizations can include modern programming languages into models for swift deployment, removing DevOps blocks.

- Artificial intelligence and machine learning continue to create value streams across different industries and verticals. With significant challenges standing in the way of AI Integration, the three-day Machine Learning & Artificial Intelligence summit features free talks and presentations from industry experts to help successfully break through barriers and take your analytics strategy to the next level. Join live or on-demand to discover the advantages of incorporating advanced analytics into your business strategy, and learn exactly how to do it from the world’s leading BI experts.in the form of live webinars, panel discussions, keynote presentations and webcam videos.

Where Have All The Workers Gone?

Last week, I talked about the long-term dangers that unchecked automation may bring. This week, I’m going to flip the script a bit and talk about the mysterious lack of people to man everything from high-level data science positions to Starbucks baristas and how the two may be related. After all, if robots (or AI) are coming for our jobs, shouldn’t we be facing a much looser labor situation than exists right now?

The answer turns out to be fairly complicated and has to do with everything from the pandemic to demographics to economics to, yes, those pesky little machine learning algorithms.

I tend to be a habitue of Starbucks. Of late, I’ve found their stores closing early, not because of lack of stock but instead due to lack of staff. This same story is not exclusive to the Seattle-based coffee maker, of course. Restaurants, grocery stores, delivery services, truckers, schools, airlines, and many other places have been dealing with a lack of staff by closing early, with some even forced to close venues altogether. There are localized labor surpluses, but they are usually highly specific and are notable only in that these surpluses are actually pretty typical for a healthy economy.

This last week saw a railway strike narrowly averted. While pay was a factor, a bigger factor was the fact that the industry is still dealing with people shortages that lead to long hours and staff spread thin. Where did everybody go?

There are several key factors needed to explain this:

- The retirement of the Boomers

- The shrinking young-adult population

- Residual effects of the pandemic

- The rise of virtual employment

The Retirement of the Boomers

The peak of the Baby Boom generation was born between 1953 and 1956, at a time when there were 4.3 children per family. This means that the average age of these peak Boomers today is seventy, with the oldest being nearly eighty. While ostensibly there are many people who continue to work past the age of seventy, in general, the Boomers overall have benefited more than any subsequent generation from pensions, stock options, and retirement investments. Past the age of seventy, their incentives for working full time or even part-time fall off pretty quickly. The Boomers overall are the second largest generation (Millennials are a little larger), but the numbers of Boomers, and hence the participation rate overall working in the economy, is now dropping dramatically.

What makes this even more striking is that family size (roughly a proxy for birthrate) dropped from 4.3 children to 1.7 children per couple from 1955 until 1974. The replacement rate for families is 2.1, meaning that for every couple, there are two children plus a bit more in the next generation to account for infant mortality, numbers first worked out by the Italian mathematician Fibonacci centuries before, with the bulk of that loss between 1955 and 1964. The Washington Post called this cohort the Jones Generation, because they have few if any real characteristics or interests found in those born from 1936 to 1955. You are seeing fewer people attempting to fill the same number of senior-level as those opened up by the Boomers. The participation rate is eroding on the oldest end, and this will only become more pressing.

The Shrinking Young Adult Population

On the other side of the generational spectrum, the average age of marriage has climbed from 21 to above 30, with more people either choosing not to have children or not getting married in the first place. In 2007, the birth rate peaked at just under the reproduction rate. This means that in the last three decades, the population of people 30 and under has been declining steadily.

It’s worth taking a short diversion to understand a key distinction in metrics. The number of births per thousand (bpk) provides a snapshot of how many babies are being born in a given country in a given year. It’s easy enough to measure – take the number of births in a year, divide it by the population of women in childbirth range (roughly from age fifteen to forty-five), and divide by a thousand. This figure tends to be somewhat noisy from year to year, though its linear regression is clearly negative.

Family size, on the other hand, is harder to measure, but also gives a broader measure of population growth or shrinkage. Family size is the number of children that a couple has. It assumes two parents, but gender is largely irrelevant here (it evens out). Family size changes very slowly in comparison to bpk, and usually tends to follow generational trendlines. (It also factors in immigration).

With family size below the replacement rate since about 1960, when you factor out the Boomers, the population in the U.S. (and many other countries) has been declining. However, the Boomers were a large bump, in part because it combined the higher birthrate of an agrarian society (frequently with ten or more children) with the low mortality rate of an industrial society (in which child mortality plummeted). It was so big that the population in the U.S. is still growing because of it, though it’s likely that combined attrition and the negative family size delta (family size – 2.1 children) will cause the US population to stall by 2040, even with immigration, and to go negative by 2070.

This was evident even before the pandemic, but there were other factors that masked it. The economy tanked in 2008 due to the Great Recession, so unemployment was high and persistent, meaning that those entering the workforce then faced difficulties finding work. As the economy improved, by 2014 (with a slight hiccup around 2011) the unemployment rate tightened to a historically low figure, then continued to tighten, to the extent that wage pressure was increasing. In 2020, the Pandemic hit, twenty million people were let go, and the economy went into a tailspin — but it didn’t last very long at all (about a year). With an implicit lockdown in place, and the rise of telecommuting, the difficulty that restaurants and others seeking low-skilled labor seemed to be due to people still waiting out COVID. Yet two and a half years out, the labor market has become tight enough that restaurants are closing stores because they can’t find people.

That’s because those people are no longer there. Somewhere around 2015, the participation rate began declining, because there were fewer “cheap laborers” at the beginning of the pipeline. Halfway through 2022, this has become more obvious. We are now entering a stage where the decline in the number of young adults will not only continue but will accelerate, with current trends indicating that it will become especially acute by 2040, given that after 2007 birth rates declined dramatically.

The Pandemic and the Virtual Economy

Another factor may be due both to COVID-hesitancy (fear of catching COVID) coupled with Long COVID, the debilitating systems that afflict about three people in one hundred who have had COVID (higher among the non-vaccinated). In a loose labor market, this effect would be lost in statistical noise, but with the labor market as tight as it is, this only amplifies the pain in finding workers and increases wage pressures for those who are hired. This is also partially a business model problem. Wages have lagged behind inflation since the 1990s, but inflation itself was not that noticeable a problem until the pandemic wreaked havoc on supply chains.

Younger adults are now much more likely to live with their parents until the age of thirty, meaning that the pressure is not there to need a job. People are starting families later (or not starting them at all), people are not buying larger homes, are buying fewer cars (because they don’t need them), and are not investing in children’s furniture. What’s more, house shares and communal housing is becoming more common.

This in turn is leading to another factor: because they don’t need larger incomes, what money they are making can go into virtual gigs: off-book programming projects are done online, writing articles and blogs, self-celebrity marketing, selling everything from clothing and jewelry to subscriptions to their own private channels. Individually, these don’t necessarily make for a huge amount of money, but the important thing is that it makes enough to break even – and increasingly to make a profit. Indeed, one reason why many younger people prefer not to go to work at fast food restaurants or similar places is that these have unpredictable schedules and expenses that can be more profitably managed with their own projects.

Again, by itself this isn’t a large factor. However, with a decreasing pool of young workers, the 3-5% of the workforce that this absorbs becomes significant enough to force chains to close stores.

Finally, the ability to work from home has been accelerated by the pandemic, compromising companies’ ability to keep their workers. When you are limited to the companies within a thirty-minute commute, job hopping is something you engage in reluctantly. When you can work anywhere within a three-thousand-mile commute just by firing up your laptop, you’re less likely to put up with low wages, bad bosses, and increasing job demands. It’s significant that the jobs that are losing workers the fastest tend to be those where the workers have to stay in a fixed location: restaurant workers, nurses, teachers, rail and port workers, retail salespeople, airline personnel, cleaners, etc. Managers misread the signals and employees leave, then force the remainder to work harder without raising wages.

The conventional wisdom that wage inflation (and fiscal stimulus) causes commodity inflation is likely wrong here. Inflation here has been due primarily to supply-chain problems and energy (oil and natural gas) pressures. Energy prices surged once the pandemic became endemic, and the Russia-Ukraine war caused energy prices to rise again due to speculation. However, energy prices have dropped by nearly 20% since June (and housing prices are cooling), which means that we should be seeing commodity and finished goods prices dropping in the next few months. Wages are lagging, but with high labor demand continuing to be the norm, it’s likely that wages will continue to rise through the end of the year, if not longer.

The New Normal

This takes us full circle back to automation. I’d make the contention (grist for another editorial) that we are approaching the end of an automation trend. There have been diminishing returns for automation visible now for decades. In the 1980s and 1990s, productivity improvements due to automation were huge, because human labor was replaced by computational labor. Now, we’re reaching the stage where more and more energy needs to be applied to computational models in order to gain significant improvements in productivity. This doesn’t mean that innovation will stop happening, but it likely does mean that we’re in for a period where the changes that happen are likely to be more sociological than technological.

What I expect to see is the next wave of automation will likely be more oriented around making the best use of the people that an organization has than it will in making processes more efficient. More use of intelligent drones to monitor changes in state of systems as diverse as traffic congestion, orchestration of productions, supply chain management, or delivery. Augmentative (and more learning-aware) education and training. Exoskeletons and construction bots. Organizational digital twins.

However, with all of this, one thing that will change is that the financial rewards are likely to shift from aggregators and speculators to creators and coordinators. More on this next week.

In media res,

Kurt Cagle

Community Editor

Data Science Central

DSC Editorial Calendar: October 2022

Every month, I’ll update this section with many topics I’m especially looking for in the coming month. These are more likely to be featured in our spotlight area. If you are interested in tackling one or more of these topics, we have the budget for dedicated articles. Please contact Kurt Cagle for details.

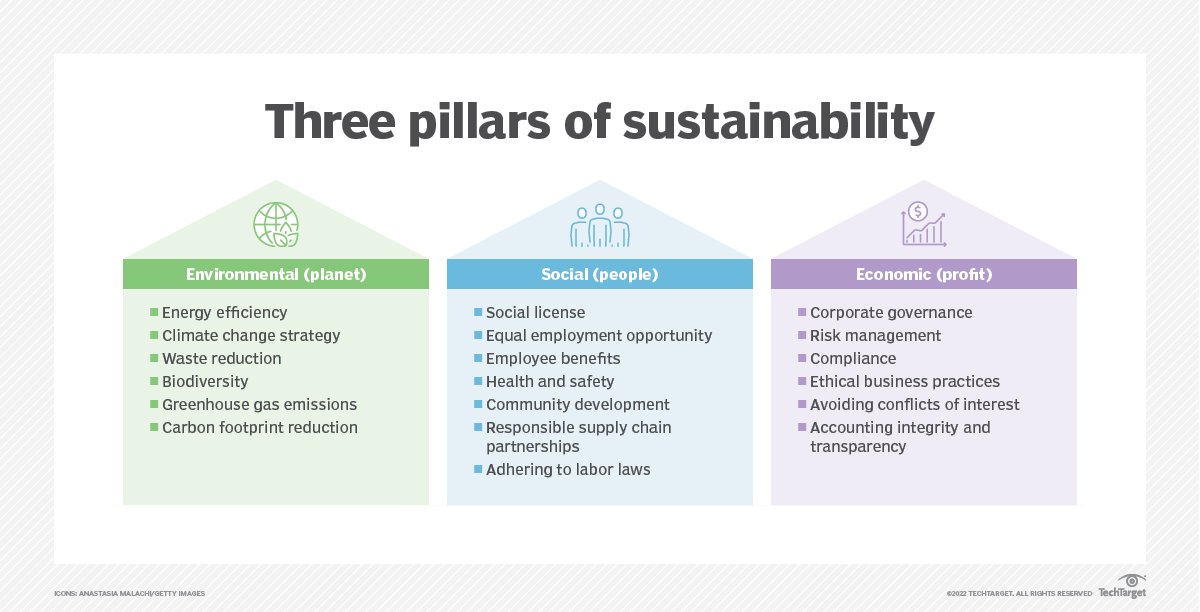

- ESG (Environment-Social-Governance)

- Digital Privacy

- The Electric Economy

- VUCA (Volatility-Uncertainty-Complexity-Ambiguity)

- Labeled Property Graphs

- Inferential Machine Learning

- Geospatial Data

- Drone Traffic Control

- Linguistic Intelligence

- Ethical AI

If you are interested in posting something else, that’s fine too, but these are areas that we believe are hot right now.

DSC Featured Articles

Picture of the Week

Tags: