Introduction

Training modern AI models has become increasingly challenging as both model size and dataset scale continue to grow. A single GPU—no matter how powerful—eventually hits hard limits in memory capacity and compute throughput. As models scale from millions to billions of parameters, and datasets expand from terabytes to petabytes, the constraints are impossible to ignore.

Rather than attempting to fit everything onto one GPU, parallelism allows us to coordinate work across many GPUs, pooling their memory and compute resources. We can then train models that would otherwise be impossible to handle on individual hardware.

What are the main types of parallelism used in deep learning today? We’ll examine the specific problems each method solves, the trade-offs involved, and when to apply each approach.

What parallelism solves

Parallelism addresses two fundamental constraints.

- Model size vs. GPU memory. As models grow, their parameters, activations, and optimizer states no longer fit on one device. Techniques like model parallelism and tensor parallelism distribute the model across multiple GPUs to increase effective memory capacity.

- Training speed vs. compute limits. Even if a model fits on a single GPU, training can be prohibitively slow. Data parallelism speeds up training by slicing the batch across GPUs and combining gradients. Pipeline parallelism overlaps work across model stages to reduce idle time.

- Communication bottlenecks. Scaling across multiple GPUs introduces communication overhead. All parallel strategies must manage data transfers, synchronization, and bandwidth constraints. Efficient training depends on both algorithmic choices and the available interconnects.

There are 5 main Parallelism Methods for AI:

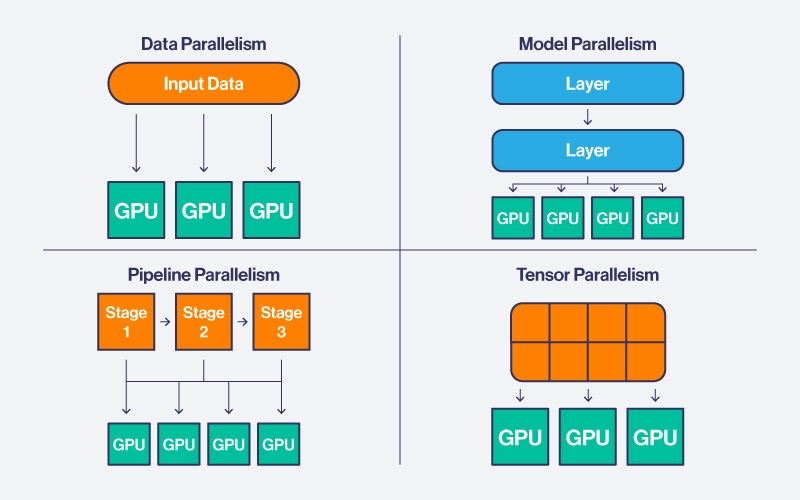

- Data Parallelism: Splits training batches across multiple GPUs, with each device computing forward and backward passes on its data portion before synchronizing gradients.

- Model Parallelism: Splits a single model across multiple GPUs, with each GPU holding a subset of layers and processing inputs sequentially across devices.

- Tensor Parallelism: Splits large tensors like weight matrices across multiple GPUs, with each device computing a fraction of operations in parallel and combining partial results.

- Pipeline Parallelism: Divides the model into sequential stages across GPUs, with inputs split into micro-batches that flow through stages like an assembly line to enable overlapping computation.

- Hybrid Parallelism: Combines data, tensor, and pipeline parallelism (often called 3D parallelism) to distribute models across devices while slicing batches and overlapping pipeline stages.

We will go more in-depth about each

Data parallelism

Data parallelism splits a training batch across multiple GPUs. Each device computes forward and backward passes on its portion of the data. Gradients are then synchronized across all GPUs before updating the model.

- Advantages: It is straightforward to implement and scales well for models that fit entirely on a single GPU. Most frameworks provide built-in support for gradient synchronization.

- Limitations: Synchronization overhead grows with the number of devices. Very large batch sizes may affect convergence and require careful tuning of learning rates. Communication between GPUs can become a bottleneck, particularly across nodes.

- Use Cases: Data parallelism is ideal for moderately sized models where memory fits on each GPU and the goal is to accelerate training through batch-level scaling.

Model parallelism

Model parallelism splits a single model across multiple GPUs. Each GPU holds only a subset of the model layers or operations, processing inputs sequentially across devices.

- Advantages: It allows training of models that exceed the memory capacity of a single GPU.

- Challenges: Splitting the model introduces dependencies between GPUs. Layer-wise or operation-wise communication can reduce efficiency, and careful mapping is needed to balance load and minimize idle time.

- Use Cases: Model parallelism is necessary when individual layers or the entire model cannot fit in one GPU’s memory.

Tensor parallelism

Tensor parallelism splits large tensors, such as weight matrices in linear layers, across multiple GPUs. Each device computes a fraction of the operations in parallel, and partial results are combined using collective communication.

- Advantages: It allows very large layers to fit across multiple devices and reduces memory duplication compared with naive model parallelism.

- Challenges: Communication overhead is significant. Operations like all-reduce or all-gather must be optimized, and bandwidth between GPUs becomes critical.

- Use Cases: Tensor parallelism is most effective for models with extremely wide layers, such as large transformer blocks, where single-layer computation exceeds the memory of one GPU.

Pipeline parallelism

Pipeline parallelism divides the model into sequential stages across GPUs. Inputs are split into micro-batches that flow through the stages like an assembly line, allowing overlapping computation.

- Pipeline Bubble: At the start and end of each pass, some GPUs may be idle, creating a pipeline bubble. Increasing micro-batch count reduces idle time and improves efficiency.

- Advantages: It enables training of very deep models and can be combined with tensor or data parallelism for higher scaling.

- Challenges: Balancing stages is critical to avoid bottlenecks. Latency can increase if micro-batches are too small or stage workloads are uneven.

- Use Cases: Pipeline parallelism is suitable for deep networks with clearly defined stage boundaries, particularly when model depth limits single-device training efficiency.

Hybrid parallelism

Hybrid parallelism combines data, tensor, and pipeline parallelism to leverage the strengths of each. Often referred to as 3D parallelism, it distributes the model across devices while also slicing batches and overlapping pipeline stages.

- Advantages: It enables training of extremely large models that neither data nor model parallelism alone could handle. It balances memory, compute, and communication constraints for maximum efficiency.

- Challenges: Implementation is complex. Careful coordination is required to avoid communication bottlenecks and ensure load balance across all dimensions.

- Use Cases: Hybrid parallelism is used in training modern large language models, where billions or trillions of parameters and massive datasets require multi-dimensional scaling strategies.

Supporting techniques

These techniques complement parallelism by addressing memory constraints, enabling efficient scaling of large models while keeping compute resources balanced.

- ZeRO and Optimizer Sharding: ZeRO reduces memory duplication by partitioning optimizer states, gradients, and parameters across GPUs. This allows training of larger models without increasing per-GPU memory.

- Activation Checkpointing: Instead of storing all intermediate activations, only select checkpoints are saved. The rest are recomputed during the backward pass. This reduces memory at the cost of extra computation.

- Offloading: Some model states can be moved to CPU or NVMe storage when GPU memory is insufficient. Offloading reduces memory pressure but introduces latency, making it most effective when combined with other parallel strategies.

Choosing a strategy & common mistakes

The choice of parallel strategy depends on model size and available hardware. When a model fits comfortably on a single GPU, data parallelism is usually sufficient to accelerate training by distributing batches across devices. If the model exceeds the memory capacity of one GPU, tensor or model parallelism becomes necessary to split the architecture across multiple devices. For deployments on large GPU clusters with very large models, hybrid parallelism offers the most flexibility by combining data, tensor, and pipeline approaches to optimize scaling across all dimensions.

- Small models (fit on a single GPU): Use data parallelism

- Large models (exceed single GPU memory): Use tensor or model parallelism

- Very large models on clusters: Use hybrid parallelism for maximum flexibility

Several common mistakes can undermine parallel training efficiency. Batch size mismatches across ranks can cause instability and unpredictable convergence behavior. Improper micro-batch sizing in pipeline parallelism reduces efficiency by leaving GPUs idle or creating bottlenecks. Additionally, insufficient interconnect bandwidth between GPUs leads to communication bottlenecks that limit the benefits of parallelism, making hardware selection and topology critical considerations.

- Avoid batch size mismatches across ranks

- Size micro-batches properly to minimize GPU idle time

- Ensure sufficient interconnect bandwidth between GPUs

- Consider hardware topology when designing parallel strategies

Conclusion

Parallelism is essential for training modern AI models that exceed the limits of single GPUs. Each strategy addresses specific constraints: data parallelism accelerates batch processing, model and tensor parallelism handle memory limits, and pipeline and hybrid approaches optimize compute efficiency across large clusters. Selecting the right combination of techniques depends on model size, hardware, and training objectives.